| Article Section | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Digital Taxation in India - International Taxation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Digital Taxation in India - International Taxation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Digital Taxation in India The 20th century has seen global trade take major strides with rapid economic integration of global economies. Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) have stretched across borders conducting business in different jurisdictions, taking advantage of differing tax laws to minimize global tax liability. International tax law has predominantly revolved around the concept of “brick and mortar” establishments in the absence of digital technology. The digital transformation driven by Information and Communication Technology has resulted in the digital economy having deep rooted societal and economic impacts and has increasingly garnered interest of States in international taxation. The OECD has characterized the digital economy as an economy having “unparalled reliance on intangible assets, the massive use of data (notably personal data), widespread adoption of multisided business models capturing value from externalities generated by free products, and the difficulty of determining the jurisdiction in which value creation occurs.”[1] The onset of the digital economy gives rise to three fundamental challenges of income attribution with regard to the concept of Permanent Establishment, the challenges are:

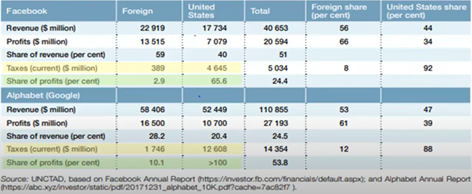

In light of these challenges and given the eroding relevance of the DTAAs given their reliance on “brick and mortar” establishments determining the taxing rights between sovereigns the international community has formed consensus that there is a need to address each of these issues to ensure a fair and transparent cross-border taxation system. The importance of sovereigns in renegotiating the present DTAAs and treaties to address the challenges posed by the Digital Economy is elucidated with reference to the revenues, profits and taxes of both Facebook and Alphabet (Google) in 2017. The table below clearly demonstrates the need for renegotiating DTAAs and the consequent disparity caused between sovereign states owing to the aggressive tax planning of MNEs in a manner that reduces their global tax liability. As per the data of the UNCTAD the following statistics are reflected.

It is submitted that in the case of Facebook and Alphabet, both companies have significantly higher revenue earned in foreign jurisdictions as opposed to the revenue earned in the United States. However both companies have paid substantially lower the taxes on foreign revenue than the tax paid on the revenue earned in the United States. For instance, Facebook earning revenue of $22,919 million from foreign jurisdictions the corresponding tax amount is merely $389 million, whereas on a revenue of $17,734 million an amount of $4,645 million is paid as tax in the United States. A similar pattern is noticed with tax paid by Alphabet (Google). This example of two technology giants aptly brings forth the dire need to address these concerns jointly as opposed to countries pursuing unilateral measures that could be counter-productive. In the midst of these challenges the OECD had explored three possible options/solutions in 2015[2] to address the challenges posed by the Digital economy, namely (i) a new nexus in the form of a significant economic presence, (ii) a withholding tax on certain types of digital transactions, and (iii) an equalization levy. A brief overview of these options is given hereunder:

The concept of ‘Significant Economic Presence’ sought to be introduced is intended to address issues arising out of a situation where an enterprise leverages digital technology to participate in the economic life of a country in a regular and sustained manner without having a physical presence in that country. Thereby extending the sovereigns right to tax in as much as the sovereign would create by way of legal fiction a taxable presence in the country where a non-resident enterprise has a significant economic presence so long as there is evidence of a sustained interaction with the sovereign’s economy through the usage of digital technology. Under this concept income may be attributed to the new nexus either through (i) revenue-based factors such as specified transactions to which the new nexus is applicable and the adoption and maintenance of thresholds; and/or (ii) digital factors such as local domain names, local digital platforms and acceptance of local payment options; and/or (iii) user-based factors such as monthly active users (MAU); online contract conclusion; and data collection where users reflect the level of economic participation in the economy of a country. However the intricacies of attribution of profits in bilateral treaties would require further examination and a lack of clarity and uniformity of views internationally in respect of attribution of profits could be a significant hurdle in the successful implementation of this new nexus theory. This concept has been introduced but not notified under the Income Tax Act, 1961 vide Finance Act, 2018 which is dealt with briefly subsequently.

The second option entails the imposition of a withholding tax on payments that are made by residents or local Permanent Establishments of MNEs to non-residents for the supply of goods or services through a digital medium. A similar concept of withholding tax is charged on royalties and fees for technical services in India. This option which partially allocates taxing rights between sovereigns with regard to income from specified transactions would require clear, unambiguous and a well-defined scope of services that would be subject to such a levy. This clear demarcation would reduce litigation, the compliance costs for the tax administration as well increase foreign investor confidence. A possible pitfall is the difficulty in applying such a tax on business to consumer (B-2-C) transactions given the cost of enforcement/compliance involved. Furthermore the current treaty obligations are a possible hindrance in the implementation of such a tax.

The third option that is explored is the introduction of an equalization levy. The equalization levy purports to tax non-residents on the basis of establishing a significant economic presence in the country. It is introduced as a measure to eradicate the disparity of tax incidence between domestic entities and MNEs. A well-defined code of what constitutes a significant economic presence would be vital for the purposes of an equalization levy. The imposition of an equalization levy is associated with certain risks such as:

This option does away with the requirement of a Permanent Establishment and levies tax on the basis of the non-resident MNE constituting a Significant Economic Presence. Digital Taxation in India With rapid digital transformation and the surge of accessibility of such technology, India’s digital economy has grown exponentially[3]. The issues observed by the OECD with regard to the Digital Economy now facing the Indian Tax administration has propelled the Government of India in instituting a high-powered committee to consider the options given by the OECD BEPS Action Plan: 1. The Government of India decided that taxing the digital economy would substantially increase the government revenue. Committee Report, 2016 In February, 2016 the Government of India vide the Committee on Taxation of E-Commerce being formed by the Central Board of Direct Taxes. This committee took special note and relied heavily on the OECD: BEPS Report on Action Plan -1 (2015). The Committee took note of each of the three possible options in the context of India. The Committee concluded with regard to the first option, i.e., the new nexus based on significant economic presence, although the necessary amendments can be effected to the provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961, the same would be rendered ineffective unless relevant treaty provisions are amended. The provisions of Section 90 (2) of the Income-tax Act, 1961, provides that the provisions of an agreement entered into by the Central Government with another country of specified jurisdiction, would be applicable to the extent they are more beneficial to the taxpayer. The Committee further observed that the second option which is the imposition of a withholding tax would also be ineffective in as much as amendments to relevant tax treaties would be required. The Committee observed that the application and effectiveness of adopting both these options in the Income Tax Act, 1961 would be restricted in scope as India is bound by the obligations made in relevant tax treaties. Given this backdrop, the Committee suggested that the imposition of an Equalization Levy was the most feasible and could be brought into effect unilaterally. With regard to the option of imposition of an equalization levy the Committee observed as follows: “110. The Committee observes that the BEPS Report conceptualizes Equalization Levy as a tax that is different from the Corporate Income Tax, and thus may not necessarily be subjected to the limitations of tax treaties. The Report does not prescribe any particular design that must be adhered to, but suggests that it could be a tax on the gross payment arising from digital economy. Such a tax on the gross amount of payment, would thus be very similar to the second option of withholding tax, except that it, not being a tax on income, would not be covered by the obligations of the tax treaties, and hence can be levied under domestic laws, even without changes in the tax treaties.” Recommendations of the Committee In light of the above observations by the Committee, the following recommendations were proposed:

This Committee Report has laid the foundation to the taxation of the digital economy in India. The Committee had observed that the purpose of the levy is to equalize the income tax disadvantage faced by Indian digital companies and facilitate an environment, where Indian digital companies can compete with foreign players without having to locate outside India. Ex-post the committee report the Government of India has proactively taken steps in addressing the taxation issues posed by the digital economy, the same is elaborated in seriatim, hereunder:

The Equalization levy was introduced in India from June 1, 2016, a tax on consideration with regards to specified services provided by non-residents in the digital sector. The digital economy is dominated by few given the network and cost characteristics, the levy corrects the unfair advantage that non-resident companies without any permanent establishments (PEs) enjoy over domestic players tempting even resident digital companies to become non-residents. A levy of 6% was levied on online advertisements, any provision of digital advertising space or any other facility or service for the purpose of online advertising. The said equalization levy would be applicable on payments made by residents carrying on business or profession or by a non-resident having a permanent establishment in India. The Government has carved out three situations under which the payment of the equalization levy would not be applicable, namely, (i) Where the Non-resident has a PE in India and services are attributable to the said PE; (ii) where aggregate consideration received by the non-resident is below the threshold of ₹ 1 lakh; and (iii) where the payment for the specified services to a Non-resident are not for the purpose of carrying out business or profession.[5] Interestingly Section 164 of the Finance Act, 2016 defines Permanent Establishment as “including” a fixed place of business. The use of the phrase “includes” means the definition given is of inclusive nature and would have to interpret by the courts broadly. The Equalization Levy inserted vide the Finance Act, 2016 has read into the scope of its provisions the provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961[6]. A brief overview of the same may be viewed hereunder:

The concept of Significant Economic Presence was introduced in India vide Finance Act, 2018 with an intent to bring the income earned by non-residents operating in digital space within the ambit of income deemed to accrue or arise in India. The Finance Act, 2018 had expanded the scope of Business Connection under Explanation 2A to Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961. The insertion of Explanation 2A to Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 clarifies that significant economic presence of a non-resident shall constitute a Business Connection in India. The criteria for the determination of a significant economic Presence is as follows:

Pursuant to the introduction of the concept of Significant Economic Presence, the Government of India has further inserted Explanation 3A to Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 vide Finance Act, 2020 with effect from 01.04.2021 (applicable to AY 2021-22) so as to provide that income attributable to the SEP would include income from[9]-

This insertion in the Income Tax act, 1961 does not deal with the concept of Equalization Levy or the concept of Significant Economic presence. This insertion is to the effect that any of the incomes that is attributable to the above three heads would be income deemed to accrue or arise in India. This insertion is therefore another tool in the box for the government has developed another mechanism to bring such activities to tax in India other than Significant Economic Presence and the Equalization Levy, with the only caveat that income from the above three activities would only be taxable only in case a Permanent Establishment is established. In addition to the insertion of Explanation 3A to Section 9(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 a proviso to Explanation 3A has been introduced with effect from 01.04.2022. This provision states that Explanation 3A would also be applicable to the income attributable in transactions referred in Explanation 2A (which deals with Significant Economic Presence).[10] It is relevant to note that this being the current position of law, the concept of Significant Economic Presence is still fairly unclear, vague and is couched in language that could go beyond the intended objective. Another argument advanced is that the threshold limits are significantly low causing unintended transactions to fall prey to such deeming provisions. The mechanism to attribute such income also requires clarity. The effective implementation of the concept of Significant Economic Presence would largely depend on treaty negotiations as the concept under the Income Tax Act, 1961 would be restricted in as much as Tax Treaties need to be modified so as to include within its ambit the new nexus concept of Significant Economic Presence. These concerns could possibly be the reasons as to why the Government has deferred the application of this concept to Assessment Year 2022-23 vide the Finance Act, 2020. Therefore from A.Y 2022-23 since SEP will be introduced, even without the existence off a PE the activities mentioned in Explanation 3A can be brought to tax and for A.Y. 2021-22 Explanation 3A will tax income only where there is an existence of a PE.

The Government of India has introduced another Equalization levy to further tackle the tax challenges posed by the digital economy. The Government of India has introduced an equalization levy at the rate of 2% on non-resident e-commerce operators who own, operate or manage digital or electronic facilities or platforms for online sales of goods or online provision of service or both[11]. Any income that is subject to either the Equalization Levy of 2016 or Equalization Levy of 2020, such income shall not form part of total income for the purposes of computation under the provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961 ensuring no double taxation of the said income in India. This would be applicable for B-2-C transactions as well. It is pertinent to note that the earlier Equalization Levy introduced vide the Finance Act, 2016 has not been withdrawn and both levies are currently applicable. For the purpose of this equalization levy, it is levied on the consideration that is received or receivable by an e-commerce operator from e-commerce supply of goods or services or both or services made, provided or facilitated by such non-resident e-commerce operator to either category of the following:

The exceptions carved out with regard to leviability of this EL is as follows[12]:

The term e-commerce supply or services was also defined in the Finance Act, 2020 to mean (i) online sales of goods owned by e-commerce operators; (ii) online provisions of services by e-commerce operators; (iii) online sale of goods or provisions of services facilitated by e-commerce operators; and (iv) any combination for the above. Interplay between Section 194(O) and the Equalization Levy The Government of India vide the Finance Act, 2020 have introduced a new Tax Deduction at Source from 01.10.2020 with regard to e-commerce operators. For the purpose of this TDS the meaning assigned to the term e-commerce operator is similar to that as in case of the Equalization Levy. In case of this TDS provision the e-commerce operator would be liable to deduct and deposit TDS even in cases where the e-commerce operator facilitates sale and the payment is made from the buyer to the seller directly. In this section the TDS is to be computed in relation to the gross amount and not the commission amount received/charged by the e-commerce operator. In brief the differences between the levies are as follows:

The Finance Act, 2021 has further clarified the meaning of the terms such as “consideration received or receivable from e-commerce supply or services’ to include the consideration of sale of goods or provision of services disregarding the ownership of such goods by the e-commerce operator or whether such service is provided or facilitated by e-commerce operators. Furthermore “online sale of goods” and “online provision of services” shall include one or more of the following online activities, namely:–– (a) acceptance of offer for sale; or (b) placing of purchase order; or (c) acceptance of the purchase order; or (d) payment of consideration; or (e) supply of goods or provision of services, partly or wholly.[13] This Finance Act further clarified that the equalization levy would be applicable on the gross receipts by the e-commerce operator and not on the commission income of the e-commerce operator. Furthermore it was clarified that any payments as royalties or fees for technical services would not be amenable to the equalization levy. Both clarifications ensure that there is no discrepancy between the domestic law and the DTAAs entered into by India. A possible issue that could arise due to the widely defined and language of the provisions there may be situations where the physical goods are bought and imported into India may also fall prey to the equalization levy. However the Committee Report, 2016 makes it clear that the equalization levy ought not to be imposed in cases of tangible goods except for the specified services. One may have fair expectations of various litigations sprouting-up in various High Courts finally culminating before the Hon’ble the Supreme Court given the lacuna and the wide ambit for interpretation given the language of the provisions. Possible Hurdles and Issues Extra-territorial Application and Situs The Equalization Levy’s being made applicable to non-resident e-commerce operators and payments made to non-residents for online advertising or the provision of online advertising space is extra-territorial in its application. However the Indian judiciary has dealt with such issues in the past and these judicial decisions would be relevant to form an opinion as to whether the Equalization Levies would be liable to be struck down due to its extra-territorial application. As per Article 245(1) of the Constitution of India the parliament is competent to enact laws with respect to the whole or any part of the territory of India and Article 245(2) provides that no law made by Parliament shall be deemed to be invalid on the ground that it would have extra-territorial operation. The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in the case of THE BENGAL IMMUNITY COMPANY LIMITED VERSUS THE STATE OF BIHAR AND OTHERS - 1955 (9) TMI 37 - SUPREME COURT which relates to the power of state governments to levy a tax on sales. The question that arose here is that when a sale transaction occurs across different states, which state would have the power/jurisdiction to tax such a sale. It was observed in the context of taxing rights between states, that Clause (1)(a) of Article 268 the question of situs of sale is addressed and is framed in a manner so as to ensure against any mischief of multiple taxation by the States on the basis of the nexus theory. The Court further went on to observe: “The situs of an intangible concept like a sale can only be fixed notionally by the application of artificial rules invented either by Judges as part of the judge-made law of the land, or by some legislative authority. But as far as we know, no fixed rule of universal application has yet been definitely and finally evolved for determining this for all purposes.” It is interesting to see that the Hon’ble Supreme Court had addressed such an issue in the 1950’s whereas currently we are faced with a similar issue. The Court in this case stated that if the States purport to impose tax on sales taking place outside the state on the ground that certain elements of the sale have a nexus to such State, similarly the other elements of sale would lie outside the state. In such a scenario the States action of adopting legal fiction to bring those elements of sale outside the States jurisdiction as sales taking place within the state and thus levying a Sales tax on an inter-state transaction; the Court held that such a deeming fiction adopted by State Legislatures is invalid and ultra vires to the Constitution of India. The observations made in this judgment are seemingly relevant to the issues of bringing to tax the digital economy. In this context a similar question of law arose for the consideration of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of GVK INDS. LTD. & ANR. VERSUS THE INCOME TAX OFFICER & ANR. - 2011 (3) TMI 1 - SUPREME COURT The facts of this case related to an assessee who had made certain payments to a foreign company and we held to be liable to withhold tax on the said payment. The questions that were considered by the Supreme Court were as to whether the parliament had the power to legislate laws on the aspects that have arisen outside India in the absence of any connection with India and as to whether the Parliament can legislate for any territory other than the territory of India? The Supreme Court in this case had held that a law that has sufficient nexus with India, although having extra-territorial aspects or causes would be within the domain of legislative competence of the Parliament unless the Constitution of India specifies otherwise. Thereafter in the case of THE TATA IRON & STEEL CO., LTD. VERSUS THE STATE OF BIHAR - 1958 (2) TMI 29 - SUPREME COURT dealt with the meaning of sufficient nexus and provided a rationale that for nexus to be sufficient the following factors should be taken into consideration:

Given this position of law, it would be interesting to see as to how the Government of India in a court of law can positively prove that there is sufficient nexus and connection with India. Treaty Provisions – ‘Scope of Taxes’ With regard to the existing Treaty provisions that are currently in force, Article 2 of the DTAAs or the OECD Model Convention dealt with the scope of the taxes that are covered under the said treaties. Interestingly this Article covers ‘identical or substantially similar taxes'. The question that could arise is as to whether the Equalization Levy introduced by India could be considered to be identical or substantially similar taxes. On the contrary, Section 90 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 through which Tax Treaty benefits are derived under the Income Tax Act, 1961 are applicable only to the taxes levied under the Income Tax Act, 1961, therefore the Equalization Levy would not be in conflict with the Treaty benefits. The Equalization levy is substantially similar to the Withholding Tax. The fact that the Equalization levy is levied on consideration as opposed to the net income is not the most versatile argument. Furthermore “gross receipts” is in the nature of income only being saved from other deductibles, therefore there is a substantial similarity as well. Additionally computation on the basis of gross receipts is also explicitly allowed for in DTAAs as in the case of Dividends (Article 10), Interest (Article 11), royalties etc. Hence this differentiation on the ground of gross v. net receipts would be exposed to vulnerabilities. CONCLUSION The Government of India taking cognizance of the revenue loss caused to the government exchequer, taking cue from the OECD: BEPS Action Plan had formed a High-Powered Committee to examine the aspects of Action Plan 1: Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalization. The unilateral measure recommended by the Committee and adopted by India seems to be a ‘quick fix’ remedy to tax the seemingly large digital economy. The introduction of the Equalization levy shows that India will tax non-resident MNEs even without establishing a PE. The introduction of the Significant Economic Presence in the domestic legislation is positive and hints India’s intent to amend tax treaties so as to include within its ambit the concept of Significant Economic Presence. The issues in its immediate implementation are prolonged deliberations to amend existing tax treaties. In an effort to side-step the prolonged treaty negotiations the Government of India introduced the Equalization Levy vide the Finance Acts providing for ease of amendments and quick adaptability of the provisions. The Committee contends that by introducing the Equalization levy in the Finance Acts as opposed to the Income Tax Act, 1961 as it would keep the levy beyond the purview of the DTAAs. The Equalization levy avoids some of the issues that arise with income attribution for the purposes of a nexus that is based on significant economic presence. While these options and methods should be explored in the next couple of years, such a “quick-fix” measure could cause further distortion and inefficiency. The Government of India should ensure that temporary measures do not translate into permanent measures. [1] Chapter-1, Pg.16, OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20, Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241046-en [2] OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20, Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241046-en [3] In February 2019, the Indian government released a report highlighting the considerable economic opportunities from digital technologies and a detailed action plan for realizing them. India’s Trillion Dollar Digital Opportunity, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India, February 2019. [7] Ministry Of Finance, Department of Revenue, CENTRAL BOARD OF DIRECT TAXES, NOTIFICATION NO. 41/2021 dated 03.05.2021. (w.e.f. 01.04.2022). [8] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [13] Explanation to Section 164(cb), Part XV, Finance Act, 2021.

By: Aryaman Ghulati - June 19, 2021

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9911796707

9911796707